Singing in the Darkness, Howard Belling

Vale Howard Belling

It is with sadness that we note the passing of jazz legend Howard Belling. In celebration of his life we have published below the profile on Howard that was first published in Dingo Issue 2.

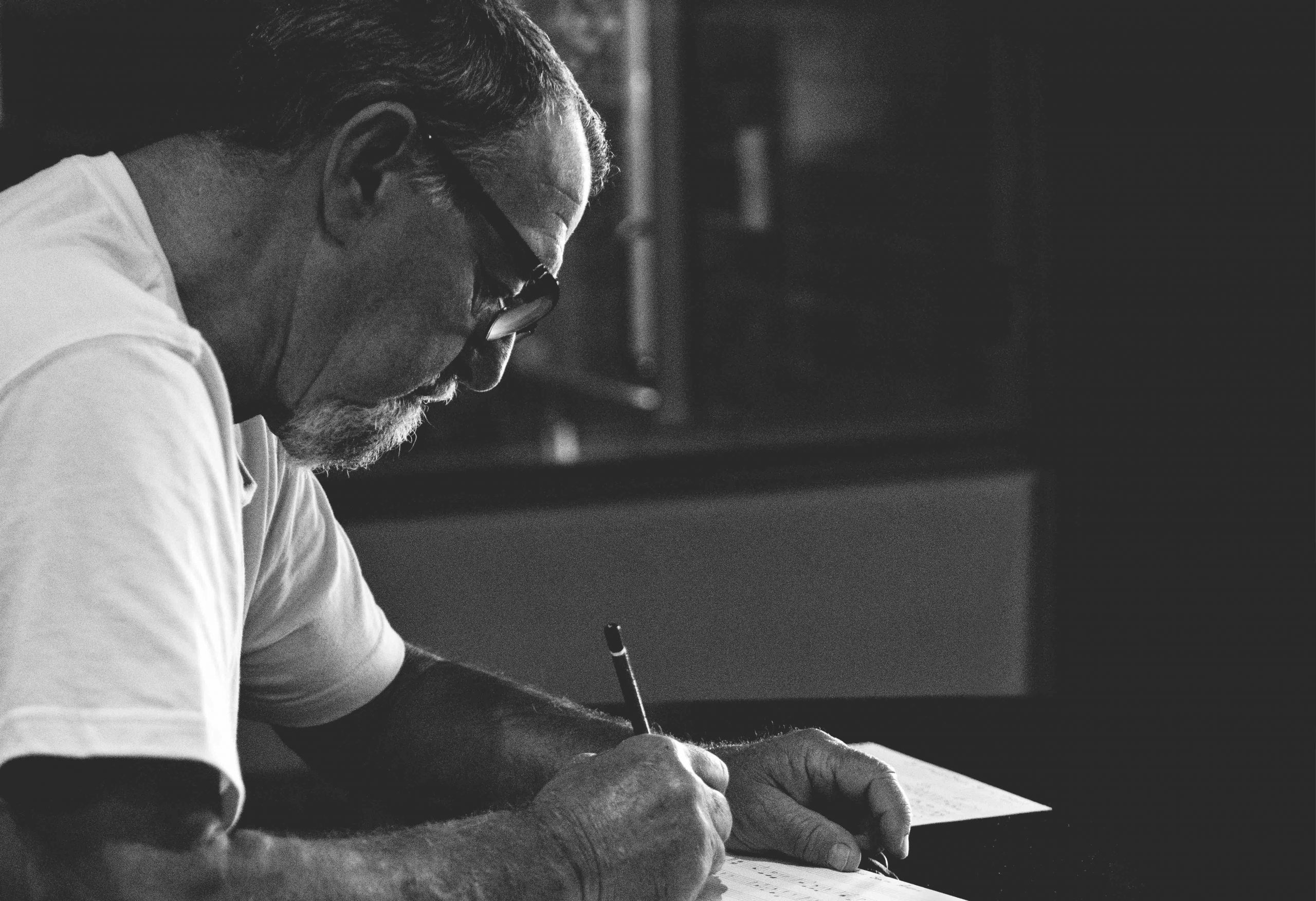

Words written by Denis Curnow

“Suddenly, I couldn’t play anymore,” he recalls. “The neurosurgeon at the Austin suggested that it might be due to pressure on my spinal cord, so they operated.”

The surgery itself was nothing short of outrageous, according to his daughter, Fem Belling. “It’s usually a six-hour op, but because he’s an old man, they had to do it in half the time,” she explains. “They take your vertebra out, go into another room, grind it down to the right size and pop it back in.”

But that was the easy part. Howard now faced the long road to recovery, which began with learning to walk again, and could only be “philosophical” about his situation, stoically accepting that his playing days, spanning eight decades, were likely over.

Putting the “struggle” into music

Half a century earlier, and half a world away, Howard was navigating through a period which history will show to be one of the most divided in apartheid-era South Africa. An attorney by day, he “wasn’t enamoured with the ‘business’ of law” – he regarded the trade as being driven

by billable hours over the genuine pursuit of justice. So it was at night that he really shone, as a pianist tearing up bars and nightclubs in his rapid rise in the South African jazz scene.

The South African struggle against apartheid from the 60s to the 80s was “the moment that South African jazz emerged as a sound and as a culture,” according to Howard’s son Zvi Belling, in the same way that the civil rights movements of the 40s and 50s shaped American jazz. “That moment

in time will always be referred to by subsequent generations as the tradition of African jazz, and my dad was right in the thick of that. He did it during the dark days when it didn’t look like there was ever going to be any freedom, yet people fought and resisted, and put the struggle into music.”

Music was “absolutely important” and “always therapeutic” in those times, according to Howard. “You have to be in South Africa to understand the role of music,” he says. “They would sing in the darkest times, and they would dance and be happy.”

But beyond its therapeutic role, jazz was a political weapon in the anti-apartheid movement, accordingto legendary South African drummer and Howard’s lifelong musical collaborator, Brian Abrahams. Musicians like them took great pride in supporting the Struggle and providing a musical service to it at rallies. As a result, many protest tunes arose and became anthems for freedom and justice, such as “Yakhal’ Inkomo” by Winston “Mankunku” Ngozi. Its title translates as “the bellowing of the bull, its final cry as it heads to slaughter”, which Mankunku said was the sound of his people.

Another such tune was “Mannenberg” by Abdullah Ibrahim. “Can you imagine a jazz song with no words? Whenever this would have been played, as soon as the first two bars were recognised by the audience, the entire venue would stand up and put up their arms in a power salute showing they supported the struggle and the downfall of apartheid,” Zvi describes. “How is that, that music can get so loaded with that kind of power? It only happens rarely in the world.” days when it didn’t look like there was ever going to be any freedom, yet people fought and resisted, and put the struggle into music.”

Challenging the apartheid establishment

Despite the spirit of protest championed by musicians, the music industry was plagued by the separatist policies of apartheid. Black and white musicians were forbidden from playing together, which drove many mixed- race bands out of the country. For that reason, along with concern about his young children growing up in an environment where the “toxicity of apartheid” was taught in schools, Howard left South Africa.

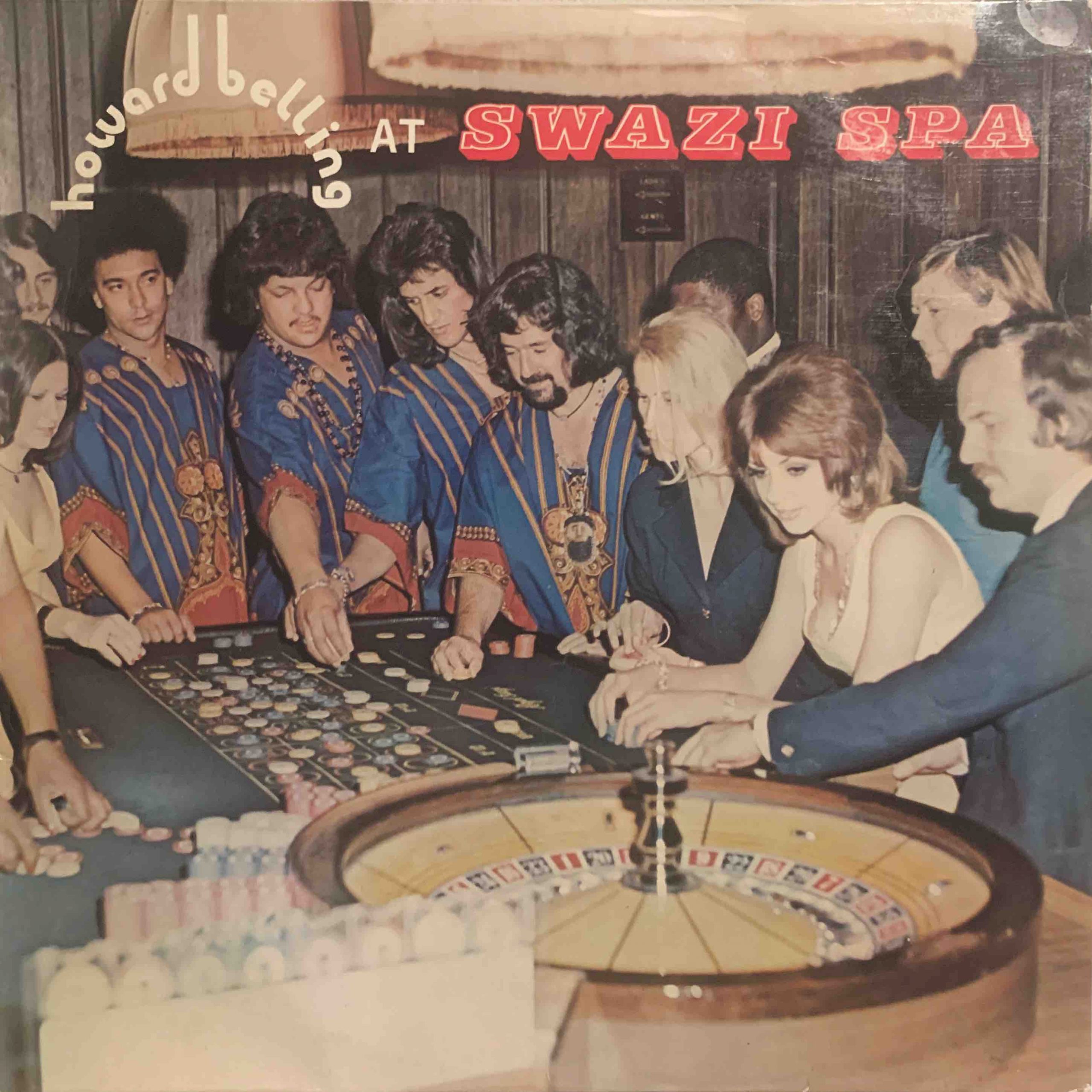

He would move to Botswana then Swaziland, where he built a name for himself and his highly successful Howard Belling Quartet. For seven years, they played in residence at grand hotels and shared the stage with artists such as Ray Charles and Sarah Vaughan when they toured. As the band grew in fame, venues began offering more and more lucrative contracts – one such offer came from a nightclub in Johannesburg. But there was one problem. “Brian Abrahams was in the band. And what’s the problem there? Brian Abrahams is ‘coloured!’ And this was apartheid South Africa,” Howard explains. “So, I went to see my friend, Jimmy Kruger, who was then the Minister of Police (I gave him his first brief when he joined the bar in Pretoria, but this was totally different). I said, come on man, give us a licence to take this band. ‘They must go and play their music in their own places,’ he says. Wouldn’t let us go.”

“So Howard said, ‘Thank you very much, I’m not interested in your contract. If I can’t bring the drummer that I have, I do not want to come and play in your club,’” Abrahams recalls. “I really respected Howard very much for being so good at that time. He saw that it was an injustice, and why should he sign the contract and replace one of the musicians just because [of] their skin colour?”

Having experienced firsthand the injustice that riddled the music industry, Howard set out with the memories of his legal training to rectify the situation. He began by working pro bono to help those musicians who had been excluded from the all-white union, by negotiating on their behalf with recording companies who had been taking advantage of them. Over the course of two decades, he worked his way up to the point where he was running the union and decided to challenge the very structure of the industry. “I couldn’t stomach the fact that you had your great lot of white musicians and your great lot of black musicians, and they seldom got together,” he recalls. “There was a white union, so I kept saying, invite the black guys too. ‘Oh, we can’t do that,’ they’d say. So I said, ‘Nonsense! It’s got to stop. We’ve got to have one union for everybody.’”

Howard pressed on, facing hostility from both sides – conservative white musicians who refused to let go of apartheid culture and nationalistic black musicians who wanted to “tear down the old house before we can put up a new house”. For five years he tirelessly chipped away, gathering support almost for no money before he finally prevailed, at long last writing and signing the constitution for the newly established, racially united Musicians Union of South Africa.

A teacher like no other

Around the turn of the century, Howard’s mother-in-law’s health was declining but, as an Australian, she could receive free healthcare here. Without a second thought, and despite being almost 70 years of age, he and the family “just uprooted and came to Melbourne”.

Soon after, the late great Brian Brown, in whose band Howard had played when he visited Melbourne in the 70s, called him to tell him that Scotch College was looking for a jazz teacher. As a muso who had learned the traditional way, by “paying

his dues” on the bandstand without any formal education, Howard was “terribly trepidatious” at the prospect, but he was talked into going for an interview.

“They said when I got there, ‘We’ve got this little sectional, come and take the thing.’ So I thought, ‘Oh, well this is where I don’t get employed,’” Howard laughs. “I open the music and what is it? ‘Sweet Georgia Brown.’ Now I know the tune! I ask, what tempo have you been taking it? It happened to be David Dower on the drums, ‘About so fast’. I said, ‘Right, let’s go guys.’ And they were terrible! So I stopped them and said, ‘For God’s sake, this, that and the other …’ And they were terribly impressed, and they gave me the gig.”

For Dower, now an internationally renowned jazz pianist and drummer, Howard was a teacher like no other. His genuine care and investment in his students’ development not only as musicians, but as people, was unmatched. “He’d invite me to his gigs in the city, and be like ‘Come down, and bring a flute from school so that you can get past the bouncer,’” he recalls fondly of his days as Howard’s first student. “So I’d carry this flute on the train and get in because I’d say I

was playing. And then he’d get me up to play as a 15-year-old with these top Melbourne musicians! In hindsight, it was probably an awful 10 minutes of their lives trying to survive playing with this kid, but for me that was just incredible. For Howard to be willing to support that, and regularly too, not as a once-off, is just amazing. It goes beyond the expectations of what a teacher normally has to do.”

And this is a sentiment shared by many of his students. Patrick Jaffe, a rising Melbourne pianist, last year released his first album, which was recorded while Howard was recovering from his surgery in hospital. “It was very important to me that he was the first person who got to hear the mix and the album,” Jaffe says. “So he was the first person I sent the link in the Dropbox to.”

Taking it slowly

In late 2019, the news of Howard’s worsening condition came as a shock to all who know him. “I heard about it because I was working with him for two years [as a teacher at Scotch], then we got the announcement that he’d ‘retired’. When I phoned him up about it, it turned out he was in hospital,” Dower recounts. “I went and visited him before the surgery, and it was probably the most distressed I’ve ever seen him, in terms of how bad it had gotten and how uncertain the whole circumstance was. It was highly distressing, I felt awful seeing him in such a state and hearing about the surgery he was about to go through and the 50/50 chance that it would be successful.”

It seemed almost certain that Howard would never play again, according to his children, and to exacerbate the loss of his own ability to perform following the surgery, Melbourne’s lockdown came just as he was discharged from hospital. Live events came to a screeching halt, meaning he was also unable to go out and enjoy other people’s gigs in what his daughter Fem calls a “music cold turkey”

“Howard would never admit he was feeling depressed about it. But his zest for life and his zest for getting up every day had definitely diminished,” she says. “I think he would argue with me saying that it’s not depression, because he had his family and everything else, but you can’t sort of quantify the loss of music against other things. Only musicians get that.”

But Howard was determined, and he was patient. Around May 2020, he started practising again. Progress was slow – there were good days and bad, and he had limited control over his fingers. But his will stood strong – as it did when Jimmy Kruger told him he couldn’t play with a coloured drummer, as it did when record companies and musicians of all creeds opposed his push for justice and unity against apartheid. In the face of this ultimate challenge, he took counsel from his wisest piece of advice – “Take it slowly. Practise slowly first, and it’ll gradually come right. Then gradually build it up.”

In June, Dower called him to see how he was doing. “He picked up the phone and played me a chord he’d just discovered,” Dower reminisces. “That was his way of just letting me know he was back.”

In late November, over a year since Howard last played, Fem and Zvi booked a return gig for the family. It was a small private gig for just their nearest and dearest. Fem had tried to ease the pressure on him in the lead-up, telling guests to lower their expectations as he was still recovering and was out of practice. And then came the gig.

“He made a liar out of me! He went out there and played like an absolute mofo!” Fem exclaims. “Howie just gets to the piano and starts ripping out these solos, just playing like the Belling legend he is. Over a year of not playing together, where we’d been playing every week. There was something amazing about that. It really is an extraordinary thing to get to make music with your family.”

Late in the night, a weary Howard’s eyes lit up as he was joined onstage by some surprise guests. “Here we have Howie’s legacy!” Fem declared to the crowd. Flanked by his former students Patrick Jaffe and Jonathan Cooper, and his children, Fem and Zvi, he played tune after tune, before finally retiring back into the crowd. The others continued, just enjoying being able to play together again, and dedicated to their beloved mentor the final tune of the night – “Yakhal’ Inkomo”: the bellowing of the bull, the cry of a people facing all the world could throw at them, a glimmer of hope in the darkest times.

What a legend, and an incredible legacy.

Howard played at my wedding when he was with Solomon and Nicholson when he was still studying was great fun, we were arrested one night at the 3 monkeys dive in pretoria as he had some black players in his band.

Howard made a great contribution to the Scotch College jazz scene, and, through his many students (including my son, Matthew) to music more broadly. Many of his students continue to play, whatever field of work they have ended up in. Howard had a wonderful way of welcoming students – it didn’t matter whether or not they were gifted, or how much work they had done; when they walked through the door, they would be greeted by Howard who would always be pleased to see them, and then they would make music together. His reports always had a lovely avuncular tone. We all loved to hear him play, and were all keenly aware that when he was playing, we were in the presence of someone very special. Howard’s name will live on in the perpetual prize (an official prize) given in his name annually; “The Howard Belling Prize for Jazz Studies”, which, until recently, he presented at the annual Jazz Cabaret. Thank you, Howard.

R. I. P. Howard. Wonderful memories of the Howard Belling Quarter at The Royal Swazi Spa at Gigi’s! A great memory too of us in the above photograph as well. Those were incredible days!!

Thanks for your blog, nice to read. Do not stop.

Howard and I were childhood and boyhood friends in our days in Pretoria. Our parents were great friends and the families met often. We both had our tonsils removed when we were about 5 years old. I can remember the 2 of us chasing each other and leaping from bed to bed in the Pretoria general hospital. We had a piano and I’m almost sure that Howard discovered piano keys in our house. We moved to Johannesburg and we lost touch. We met for the last time at the spa in Swaziland.