High Bebop, Vol 1 is a recent release by Western Australian artist Austin Salisbury featuring the music of pianist Bud Powell. Reproduced below (with thanks to Austin and Marinus) is an article exploring the origins and context of the musical content on the release.

You can check out the music at Austin’s bandcamp.

HIGH BEBOP, VOL 1

Three selections from the music of Bud Powell, arranged and performed by Austin Salisbury (piano), and featuring Alistair Peel (double bass) & Peter Evans (drums)

A written accompaniment outlining the social and political context of the Be-Bop era

MARINUS SCHIMMEL

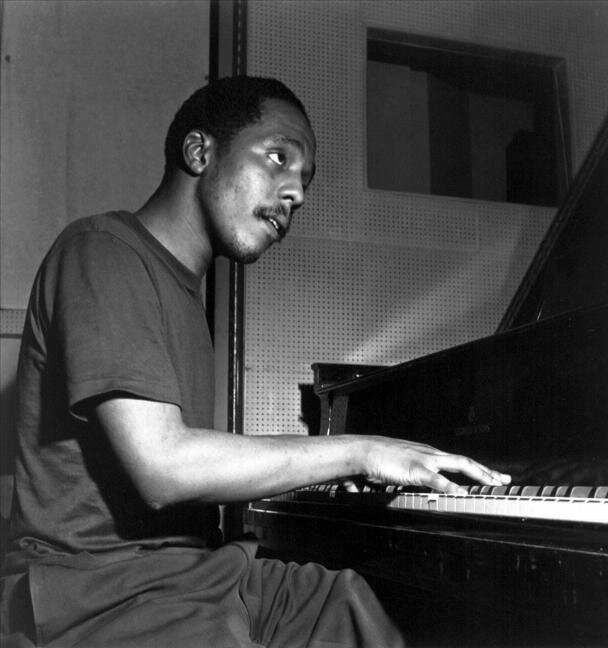

Bud Powell was born in Harlem on the 27th of September 1924 and died on the 31st of July 1966. His life began in the early years of the Harlem Renaissance and ended just as the Black Arts Movement was beginning to flourish.

Powell lived during a turbulent period in American history, encompassing the struggles of the Great Depression, the musical revolution of Be-Bop, and the tremendous activism of the Civil Rights Movement each of which followed on from the social upheaval caused by World War Two.

The Harlem Renaissance is one part of a much longer history of Black emancipation. It was a cultural, artistic, and political movement associated with writers such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, and musicians such as Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday.

Harlem was the epicentre for this flourish of Black cultural expression and political awakening thanks, in part, to the migration of Black people to the neighbourhood as part of a mass exodus of African Americans from the South.

Between 1910 and 1940 approximately 1.5 million African Americans migrated north in what is known as the First Great Migration. This was motivated by a desire to seek new economic opportunities and to escape the terror of the Jim Crow South. In the industrialising North, many factories that historically discriminated against Black people faced a labour shortage due to the large number of white Americans drafted for the war effort. In addition, over 300,000 Black men enlisted to serve during the first World War in what some have characterised as an attempt to gain respect and full citizenship.

When the war ended, white soldiers found their jobs taken and Black soldiers found they remained subject to racial prejudice. W.E.B Du Bois, a founding member of the NAACP, summarised the situation faced by Black returning soldiers in May of 1919 as follows: “We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting.”

The social unrest and tension associated with the shifting racial make-up of cities and difficult economic conditions boiled over in mid 1919 in what is known as the Red Summer. This included over 20 race riots across the country and multiple massacres. The Harlem Renaissance can be viewed as part of this struggle – not merely a struggle for survival, but dignity, too. The movement sought to reflect the reality and nuances of African American life, instil pride in the community and challenge racism. Langston Hughes, a leader of the Harlem Renaissance, expressed the ethos that he and his artistic peers aspired to in one of his essays:

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.

Here we can see the beginning of Be-Bop’s ethos. Swing was the predominate jazz style prior to Be-Bop, which was performed in big ball rooms, by largely segregated bands for white audiences. And where Black artists were included, they were often billed as ‘guest performers’ to maintain a semblance of segregation: “boy, I’d love to have you in my band” a white band leader reportedly told Dizzy Gillespie “but you’re so dark.” The music of the 1920s and 30’s, was also performed by large bands, leaving little room for improvisation, experimentation, or individual expression.

Be-Bop can be thought of as an attempt by artists to reclaim the music from the audience for themselves. Amiri Baraka, a founder of the Black Arts Movement, suggests that the artists aimed to restore the music “to its original separateness, to drag it outside the mainstream of American culture again.” Unlike the jazz of the previous era that had been “stripped of its social context,’ Be-Bop embodied a renewed impulse among performers to resist appropriation, and to experiment with new forms of expression within a supportive, albeit competitive, community.

The centrality of race and whiteness in this understanding of mainstream culture should not be underestimated. Be-Bop not only sought to reclaim the music from the audience, but, importantly for Baraka, from white people more broadly. This is not to say that white musicians were not involved – both Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie hired white musicians in their bands. However, to view Be-Bop’s origins without understanding its racial context would be to misunderstand the movement’s racial/social underpinnings.

Again, we can return to the words of Hughes to illustrate the centrality of race (and racism) to Be-Bop’s genesis:

Every time a cop hits a Negro with his billy club [the club says], ‘BOP!BOP! BE-BOP!’ That’s where Be-Bop comes from, beaten right out of some Negro’s head into horns and saxophones and the piano keys that play it. That’s why so many white folks don’t dig Bop… white folks do not get their heads beat just for being white. But me, a cop is liable to beat my head just for being coloured.

Specific evidence for this can be drawn from Powell’s own life. Late one night outside a Philadelphian nightclub in 1945, Powell was assaulted by police resulting in severe head injuries. The trauma inflicted by those cops hampered Powell’s mental health, physical health, and creativity until his death in 1966. 1945 also marked the end of WW2 in September and the first taping of Parker’s Savoy sessions in November.

A complex combination of demographic and economic changes in wake of WW2 fostered the environment from which Be-Bop emerged. Shaped by discontent among younger performers regarding the economics of big bands and the lack of artistic freedom, Be-Bop was, according to Ralph Ellison, a writer and literary critic, nothing short of a “revolution in culture.”

The end of WW2 also saw a repeat of the dynamic faced by returning Black soldiers after WW1. One million African Americans served in segregated units during WW2 to fight against fascism overseas, despite not enjoying full democratic rights at home. According to James Baldwin, a literary icon of the Black Arts Movement, the continued disrespect paid toward Black soldiers marked a turning point in the conscious of African Americans: “The seeds of the protest movement of the 1950s and 1960s were sewn.” Having returned victorious abroad, it was time for a victory at home. Baldwin would later reflect that it was during this post-war period that scepticism toward America’s promise of equality crystalised within Black communities. “To put it briefly” he wrote, “a certain hope died, a certain hope for white Americans faded.”

The Civil Rights Movement, often associated with Martin Luther King Jr. and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, is the most familiar part of African American political struggle. It emphasised a Politics of Respectability, opposition to segregation and non-violent protests. The Black Power movement gained traction in the later years of the Civil Rights Movement. Prominent figures like Malcom X thought that while desegregation may have integrated schools, it failed to liberate Black Americans from poverty or ensure their protection from police brutality – an issue that continues to resonate in the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement.

The Black Power Movement helped popularise phrases like ‘Black is beautiful’ when promoting Black political and economic independence. With this renewed political project came the second iteration of the Harlem Renaissance, known as the Black Arts Movement. This, according to playwright Larry Neal, was “the aesthetic and spiritual sister of Black Power.” Or, in musical terms, the artistic accompaniment to the political activism of the era that began with the assassinations of Malcom X and MLK in 1965 and ‘68.

I use the word accompaniment deliverately to follow the work of Professors Barbara Tomlinson and George Lipsitz , who coined the term as a guiding metaphor for their scholarship and activism. To accompany others, musicians do not simply play more. Rather, accompaniment requires being attentive to, and cooperating with others; Sometimes it requires playing less (read: saying), so that others can be heard.

The social and political context in which Powell lived have changed dramatically in the years since Be-Bop’s heyday, however the turmoil of recent years has revealed that racism and other forms of discrimination remain. The consequences of such discrimination are severe and, sadly, we need not look to America for examples. The inequalities arising from Australia’s violent ‘founding’ reverberate today and have largely been met by a great silence. In reworking Powell’s music for a contemporary audience, and including this written accompaniment, Austin Salisbury directs attention to the conditions from which Be-Bop emerged to resist stripping the music of its social context once more. In doing so we encourage artists and listeners (and readers) to reflect on their own potential to challenge all forms of discrimination. As Lipsitz and Tomlinson state:

The indignities, injustices, and indecent social conditions of our time will not change without a fight. Yet the practice of accompaniment can make a difference.

No one person can be expected to do everything. Rather, everyone has a part to play.

— Marinus Schimmel

NOTES AND INSPIRATION

Baraka, Amiri. 2002. Blues people : Negro music in white America. New York: Perennial. Original edition, 1969.

DeVeaux, Scott. 1997. The Birth Of Bebop: A Social and Musical History. Berkely, California: University of California Press.

Hughes, Langston. 1985. “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” The Langston Hughes review 4 (1):1-4.

Tomlinson, Barbara, and George Lipsitz. 2013. “American Studies as Accompaniment.” American quarterly 65 (1):1-30. doi: 10.1353/aq.2013.0009.

High Bebop, Vol. 1.

Austin Salisbury, piano, arrangements. Alistair Peel, double bass.

Peter Evans, drums.

Track 1: Dance of the Infidels (6:01)

Track 2: Celia (4:55)

Track 3: Hallucinations (3:18)

All compositions by Bud Powell. Mixed & mastered by Kieran Kenderessy. Recorded at Loop Recording Studios on the 21st & 22nd March, 2022